By E. S. Pope

Death is scary for our culture. We don’t talk about it until we literally have no other choice, no way to avoid it anymore. And oftentimes, by then, it’s too late. We don’t know what our loved ones want or don’t want for treatment, for final arrangements. We don’t tell them all the things we want to say before they can’t answer back. At least, that’s what happened to me with my grandmother, leaving me with only her favorite broach and a lifetime of regrets. Her death spurred me to work with the terminally ill in the first place, to guide others to avoid those same mistakes.

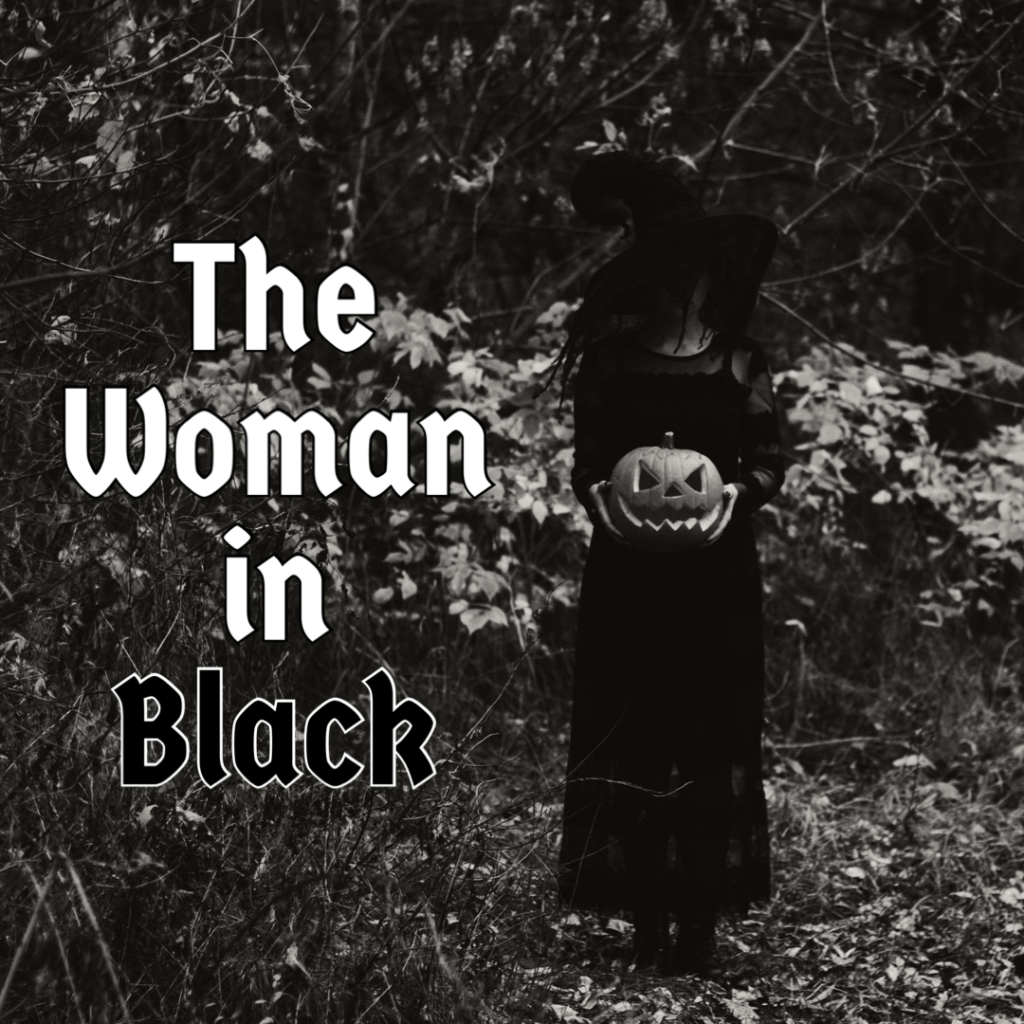

I’d been working in hospice for fifteen years the first time I saw the woman in black, back when I still could stomach that kind of work. I’d left my patient, Betty’s, house and winded my way out of her neighborhood. Beside one of the last houses, I saw a woman standing by the corner. I raised my hand to wave automatically like all good neighbors do, but stopped halfway, my hand going limp. The woman wore all black with a dress that covered her ankles and arms and a black wide brimmed hat. A black cloth, probably some kind of veil, obscured her face. She stood still as a sentry, tensed and waiting for the ambush. Then, as quickly as she’d appeared, she was gone in my rear view mirror as I turned onto the main road.

I shook my head, trying to erase the image out of my memory like an etch-a-sketch but I found little success. Eventually, my numb hand found its way back to the steering wheel. I picked up the speed and focused on getting home. I didn’t want to think about the antiquated black clothing she wore or the staring stillness that she offered to my half-hearted wave. There was something empty about the woman’s presence but I couldn’t put my finger on it at the time.

Thirty minutes later, my phone buzzed. The caller ID showed the main office. They called for one of two reasons: a patient and family in crisis or a death.

It turned out to be the latter. Betty died at 4:02 PM, about 5 minutes after I left her room. Cursing under my breath, I flipped the car around in an empty lot and headed back to her home to pronounce her. I scanned the lawns as I drove back into the neighborhood for a sign of the strange woman in black but saw nothing out of the ordinary. The oddest thing was the lack of people outside, but such were the times.

After pronouncing Betty dead, filling out the paperwork, comforting the family, and ensuring the funeral home came to remand the body, I headed home again, albeit two hours later. It was hard to shake the out of place image of the woman in black as I drove.

As soon as I got in the door, I kicked off my shoes, threw my stuff in a corner, and collapsed onto the couch. I had no energy for anything more active than raising food and drink to my mouth. I could’ve used a beer but I’d sworn those off years ago, long before I became a nurse. After laying there for hours, sleep finally melted away the image of the woman in black in an amber colored rain.

___________________________________________________________________

Days dragged by and I continued my job in hospice. One of the worst parts of my line of work is on-call shifts, often brutal twenty four hour shifts, where you’re called all over the state to put out fires that don’t respond to a conventional extinguisher. We’re talking patients with suicidal intent, violent or mentally exhausted caregivers, missing drugs, broken bones, deaths, you name it. We’ve got it all. I think it created one of hospice workers’ favorite sayings: ‘You can’t make this shit up.’ And it’s true. You’d need an imagination the size of Jupiter to put it all together.

This particular night netted me a fairly tame call. A patient’s daughter, Darcy, was freaking out. Her dad sounded all congested and was having a hard time breathing. She thought he could die at any minute. I took that statement with a grain of salt. I could season an ocean with the amount of times I had been called out by a scared family member crying “death”. But it’s all good, I get it. I don’t judge.

Forty-five minutes after hanging up, I had squirmed into my scrubs and boots, plowed through the snowy roads, and safely arrived at Darcy’s modest mid-state home. She ushered me in with shaky hands.

“Okay, hun, tell me what happened,” I said once we reached the kitchen.

“I don’t know,” she said, trembling. “One minute, I was feeding him a hamburger and the next he started choking. His face got so red. I just didn’t…”

“It’s okay. You’re okay,” I said. “You didn’t do anything wrong. Your dad gets food for comfort and this is something we know might happen. He can’t swallow the same way he used to.”

Darcy started crying. “All I can hear is his breathing, no matter where I go in this damn house. It sounds so horrible.”

I put a reassuring hand on her shoulder and said, “Here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to go in there together and I’m going to check him out. We’ll come up with a plan, I’ll show you what to do, then I want you to take a walk.”

“In the snow?” She asked, her features twisting.

“In the snow,” I nodded, “It’s cold. It’s quiet. It’ll straighten your head right out and give you the breather you need. Sound like a plan?”

She nodded and gulped hard, then led me down the hall.

Mr. Radochev looked about as good as he sounded, which is to say, like hell. His lungs rattled every time he breathed in, over thirty times a minute if my count was right. The congestion was audible and he was running a fever.

“Looks like an aspiration pneumonia, unfortunately,” I said and proceeded to pull the bed pad to rotate him onto his side in one smooth motion. The rattle became quieter in an instant, almost beyond hearing. “The good news is that putting him on his side should help. I think it may be time to give him his scheduled meds.”

Darcy paled. “You’re going to… to… put him out of his misery?”

“We ease, we don’t euthanize, and I promise you, none of his medications are meant to speed his death. What it will do is slow his breathing and make him much more comfortable. The rest is up to him.”

I guided her in how to draw up syringes and put the medication in his cheek to be absorbed, then said, “I think it’s time for that walk,” and ushered her out the door as she grabbed for her coat and hat.

I sighed with relief the moment the door shut and peeked back in on Mr. Radochev, who already looked ten times better. Then, I let myself onto the back deck for a breather of my own.

The bright moonlight cast long shadows from the trees, like night sentries, stark against the snowy white ground. Fog hovered above it, causing an ethereal bending of shadowy shapes at the forest’s edge. My breath puffed out another sigh and my own small cloud of fog obscured my vision for a moment.

When it cleared, I saw a new shape, a black silhouette standing in the crisp white that left no shadow.

I cleared my throat and managed a half-hearted, “How was your walk, Darcy?” But, I knew. It wasn’t Darcy.

The woman in black stood closer this time, maybe twenty or thirty feet away. I could make out the shape of her ruffled dress and her large brimmed hat but all other details blended into the night. Once, I thought I saw moonlight glint in her eyes but it must have been a trick of my sight.

“Who are you? What do you want?” I called. “Just tell me,” I whispered under my breath.

The woman in black stood silent as the shadowy trees, a sentry of darkness in her own right, watching and waiting for something I couldn’t see.

Something, whether a sound or feeling, made me rip my eyes away from the woman and turn towards the house in the direction of Mr. Radochev’s room. Out of nowhere, a terrible scream rent the night with sharp, stabbing claws. The sound assaulted me like a stab in the back and I whirled around.

The woman in black was gone. The dark trees danced in the wind without sound. Ten, twenty, thirty heartbeats later, no more screams or wails came. I reassured myself that it must be a fox or fisher cat. Breath hitching in my throat, I went inside to check on my patient.

His rattling had improved, so much so that I didn’t hear a sound. It took a second for my mind to click, to banish the woman in black enough to process the silence. Sure enough, I found Mr. Radochev in his bed, no longer breathing. Time of death: 11:22 PM.

I heard Darcy’s sobs rattling around my mind the whole way home. I couldn’t stop her pleas of “no, not yet,” and “Daddy, come back.” while I calmly explained in the background how some people wait until a loved one leaves to die, usually feeling they will protect them. Somehow, the moonlight-bathed snow only made the night seem darker on that drive.

Nothing would drown the pleas that night, nor to take away the image of the woman in black standing in the snow. Many times, I picked up my keys and started towards the door to go to the liquor store, and many times, I forced myself to put them down, remembering I was on-call, remembering I’d been sober for seven years. I put on music, television, funny dog videos on my phone. Even then, I thought of her, staring into the gray oblivion of my bedroom wall.

Was I losing my mind? I had to ask myself. The first time, I could believe it was a strange neighbor and even stranger coincidence. The second time, however, I couldn’t dismiss it so easily. The woman in black appeared to me in a completely different town in Mr. Radochev’s backyard, in the middle of a snow storm, mere moments before his death.

I needed to sleep. Maybe, it was all a dream. Or maybe, I needed to be committed, a case of too many deaths seen in a single life. That was my blessed last thought a couple hours before sunrise as I was pulled down into the murky brown waters of sleep.

___________________________________________________________________

A few days later, I planned a co-visit with the team chaplain to visit a long term patient, Peggy, who’d been on hospice for a year. Her son let us in and left us upstairs where she sat in her wheelchair.

“And if it isn’t my two favorite harbingers of death,” Peggy cracked.

Chaplain Allen and I broke into wide smiles as we climbed the last couple stairs of the old split ranch.

“Can’t harbinge death to someone who looks like death already!” I zinged right back. I’d learned quickly the only way to keep up with Peggy was to dish her wise cracks right back at her.

Peggy faked a shot to the heart and winced. I closed the final few steps and took her hand.

She chuckled and smiled bright before asking, “How are you, dear?” She might be able to barely breathe due to her stage four heart disease but she knew what she was asking.

“I’m well,” I lied.

“You don’t look it,” she said, “If I didn’t know any better, I’d say you aged a couple years, not days, since you were here. When’s the last time you slept?”

I pushed away the image of the woman in black, summoned by the distant memory of a good night’s sleep.

“Truly, I’m fine, Peggy. The real question is how are you?”

She took the chaplain’s hand and greeted him as well, before answering through pursed lips as her talking took a toll on her breathing, “Truly, I’m fine.” She rolled her eyes at me.

I laughed again but stopped as I noticed something behind her.

Peggy looked at me concerned. “What’s a matter, dear? Seen a ghost?” She and Chaplain Allen shared another chuckle as I stood and went to the window.

Outside, the woman in black stood waiting even closer this time, no more than ten feet from the house. The sun was high and it illuminated details I couldn’t have seen that snowy night with Mr. Radochev.

Her dress buttoned neatly down the center with the bottom puffing out like an old fashioned ball gown. A black lace veil covered her face below the shade of her wide brimmed hat, making it hard to see any identifying features, but I spotted a broach of white marble that seemed oddly familiar.

Chaplain Allen’s deep voice broke through my trance. “Hey, Kimmy, you okay?” I glanced back to see him and Peggy staring at me with concern. He moved up to the window beside me, putting a comforting hand on my shoulder.

“Do you see that?” I asked, pointing at the woman in black.

He squinted as if looking far past her. “Hmm… is that a blue jay maybe?”

My heart sank. He couldn’t see it.

“No,” I said, the color draining from my voice as I followed his gaze, “That’s just a crow.”

As he shrugged and sat himself back down on the couch across from Peggy, the woman in black moved. I winced back, startled. The bottom of her veil shifted like she was moving her mouth but I couldn’t hear a sound through the thick windows. Then, her arm slowly raised, as if lifting a great weight, and she pointed behind me.

“No!” I screamed, turning to where she pointed.

Peggy clutched her chest as my gaze found her, this time not in jest, and her face screwed up in pain. Her breathing grew rapid in a blink and I rushed to her side.

“She’s having a heart attack,” I yelled.

Chaplain Allen seemed in a daze, staring towards the window. I dared to follow his gaze.

To my surprise, the woman in black still stood there, waiting, her arm back at her side. Maybe, I was wrong about the meaning of the woman in black. Maybe, Peggy wouldn’t die today after all. Maybe, this was all some crazy nightmare, I thought in rapid succession.

Then, the woman started to raise her hand again.

I screamed even louder this time, loud enough for neighbors to hear and probably come running.

Her black gloved hand pointed straight at Chaplain Allen. His eyes rolled back in his head and his mouth began to froth before he fell to the floor and started seizing. I held his head as best I could to make sure he didn’t harm himself accidentally. In retrospect, I don’t know why I did anything. I knew, at least on some level, what the outcome would be with the woman in black present.

Peggy’s son was the first in the room. He’d been outside working on his car when he heard the screams. I risked a last glance at the window, but the woman in black had vanished. The rest of the neighborhood soon followed Peggy’s son, spurred to action by my desperate screams.

I barely had time to make it outside before I heaved, my entire lunch splattering nasty brown over Peggy’s bright pink rose bushes.

“Sorry,” I said to no one in particular. Neighbors continued to rush to the front door but none paid me mind. A nurse in distress was always invisible.

My legs wobbled but I caught myself against the side of the house. A low moan like a scream caught under hundreds of feet of rock rumbled out of me. I stumbled in a daze to my car.

My eyes wouldn’t focus as I turned my car on. Everywhere I looked I saw the vague outline of a black shadow, of the woman in black. I no longer knew if it was reality or a sleep-deprived hallucination. Chaplain Allen hadn’t seen the woman, which meant I was seeing things that weren’t there, that I was crazy, right?

Sweating, I peeled away from the house. A few neighbors hollered as they jumped out of the way, some of them yelling for me to slow down. It didn’t even occur to me that they would need a nurse to call time of death on Peggy and Chaplain Allen, nor did I think of how suspicious it looked for me to flee the scene of two deaths.

Once I was home, I spiraled, tearing through the house like a hurricane, searching for any kind of alcohol I may have missed when I got clean. I gasped when I saw the boxes of my grandmother’s things in the basement. Grandma always kept a bottle of apricot brandy on hand and I’d kept the one from her house when she died as a memento.

As I sat in the darkness, I stared at that bottle, stared so hard I was surprised it didn’t start boiling. But if I looked away, I knew I’d see her there waiting, a shadow somehow stiller and darker than the rest of my room. It may have been moments or hours before I finally said screw it and gave into the darkness, gave into that craving that I acknowledged now would never truly leave me. There wasn’t time to waste. I needed to see and feel nothing, as soon as possible. Swig after swig brought me closer to nirvana until the bottle seemed to empty itself and sleep chased me into the all-consuming blackness.

I opened my eyes to bright daylight streaming across an open park field. My lunchbox bounced at my side as I marched to the closest bench then groaned as I eased myself down onto it. My body ached with a soreness and tiredness I hadn’t known in a long time. Work had been hell lately but a packed lunch in the sunshine was just the medicine I needed.

The bench’s iron stabbed cold into my back, into my shoulder blades and down my spine. I sighed and let my tired eyes wander along with my mind. At least, I tried.

Everytime I seemed on the verge of relaxing, of spacing out entirely, my body and mind hit a roadblock. It’s hard to explain but I’d describe it as an awareness, a sudden understanding that there was a dark presence like a stormcloud oozing corruption onto my body, the oily liquid slithering between my shoulders and down my back. No, it wasn’t the bench that had made me so cold when I sat down. That stormcloud raged beside me.

I turned my body, one muscle at a time, knowing all at once what I’d see and simultaneously promising myself I was insane. I saw the black frills of a funeral dress, running upward and showing no skin. My eyes followed it to a familiar white broach and a woman without a face. A laced veil obscured it. She stared off into the distance, seeming unaware of my presence.

I reached out a shaking hand and her head turned so fast I heard her neck crack. The veil flew back to reveal a rotting, blackened face, a face that I recognized even through the decay, the face of my grandmother. Millipedes skittered out of her eye sockets and into her mouth as her lips curled back and she let out a scream that could’ve shattered glass. It tore through me and I fell back off the bench, pulling my legs towards my chest in the fetal position.

The wailing seemed like it would go on forever. I could feel her, beyond the barely protective shell of my body, hanging over me and screaming the most terrible sound I have ever heard. It was the same sound I’d heard that night in Mr. Radochev’s woods.

An unaccountable time later, I opened my eyes, slow at first, fearing she’d still be there. I gasped as I saw I was no longer outside. Pale colored wallpaper and once regal manor home walls surrounded me. The sickly sweet smell of too many flowers in a stagnant room assaulted my senses and tore at my memory. I knew instantly where I was: the funeral home where I refused to say goodbye to my grandma.

I rose with effort to my feet and walked towards the overwhelming stench of funeral flowers, knowing what I would find, what I had to face. A casket laid open for viewing, stiff fingers holding a bouquet raised just above the sides. The room sat empty of everyone but me and the corpse. I forced myself forward.

The morticians had done good work. My grandmother appeared as she had at her best in recent memory. Makeup covered her face tastefully, covering up the liver spots and bruising of a dead woman. She wore a dress of pure black. It would’ve been floor length if standing would have been possible ever again. But, she couldn’t, she wouldn’t. She was dead. I had to face that fact and in that quiet moment, for the first time, I did.

I let out a deep sigh then planted a kiss on her forehead. “I love you, grandma,” I said, “And I know you will always be with me.”

I turned away from the casket and took a few steps toward the door. Movement behind me stopped me dead. No one else had been in the room. I spun to see grandma’s corpse rise forward, stiff as a board. The spikes holding her eyelids shut tore as she opened empty sockets. Her void like gaze focused on me and I fell back into the closest chair.

Then, my grandmother’s corpse spoke a single sentence in a croaking, brittle voice: “I’ll be screaming at you next.” Her jaw cracked and opened impossibly low, releasing a wail even worse than the one from the park bench. As she screamed, her skin sloughed away from her face and body, maggots falling like snow as she unraveled.

I woke screaming until my hoarse voice choked off and died in my throat. My sheets were soaked beneath me as I writhed and thrashed to stand but my legs weren’t ready. I collapsed to the floor in a boneless heap, sobbing. The burning emptiness in my chest was so great the pain of the fall didn’t even register. I missed my grandma so much and I never got to say goodbye.

I spent the rest of the night staring at the rotating blade of my ceiling fan, unable to look away, as it scarred its terrible, relentless circle, one that it seemed would never end until my alarm screamed for me to get up.

___________________________________________________________________

The next day, I traveled near the state border to see one of my favorite patients first. On a normal day, it would’ve made the rest of my day hell to schedule, would’ve mattered at all. But I was already existing in a living hell. My head pounded. My eyes were heavy. My throat scratched like sandpaper. I could no longer even trust my own mind.

I arrived in record time, somehow managing to not attract the attention of any patrolling police as I barreled down I-95 going a hundred miles an hour. Then, I skipped the facility’s check-in area. None of it mattered anyway. I was so desperate for some bit of joy today, something to remind me of why I do what I do.

My patient’s husband, Mac, met me outside the apartment. His eyes cast a somber gaze as I approached. I cursed under my breath. I hadn’t checked my email this morning. Had something happened over night?

“As you may know,” Mac began, “Millie has had some changes.”

“I didn’t,” I admitted, “But there was obviously a reason I felt I needed to come here first today.”

He favored me with a small smile. “You always have been the best part of hospice, Kim. You’ve made Millie’s final months truly special.”

I opened and closed my mouth, not sure what to say. Hearing nothing, Mac opened the door and led me inside.

We passed by countless pictures of Mac, Millie and their family on the walls, snapshots of their home in New Hampshire, trips to the lake, to other countries, of birthdays and weddings. You could read the whole story of Mac and Millie’s life together on those walls. Mac often did. I think I may know more stories of their lives than their children. My personal favorite was how Mac jokes that Millie pursued him relentlessly after meeting him on a train ride overseas, when in reality, it was the very opposite. He said Millie used to always give him a hard kick in the shins for that one.

Mac settled himself down beside Millie, cupping her face and whispering to her. I heard the occasional “I love you” and “I’m here” with other sweet nothings shared only between the two of them. Millie’s mouth hung open, sucking in gasping breaths. Her forehead glistened with the sweat of the normal fever we see when someone is actively dying. Her body was calm.

Millie had always reminded me of my grandmother. Now, she lay dying in front of me, like my grandmother dying all over again. I saw the horrible nightmares of her skin sloughing off her bones, leaving only a casket full of bones, and started back towards the door.

“Kim?” Mac asked, “Aren’t you going to check on her?”

“I’m sorry,” I said, breathless, “ I just need some air. Be right back, I promise.”

In moments, I was out in the hall. My breaths came in ragged grunts as I tried to keep from vomiting. Down the hallway, I caught half of a long black dress, disappearing behind the corner of the adjacent hallway.

“No,” I growled, “No, not this one. You can’t have her. Take someone else.”

I was running without thinking towards where I saw the dress disappear around the corner. Inhuman noises whined and grinded in my throat. I ran and ran, turning corner after corner. I would catch her this time and stop her. She couldn’t take her, not my grandma. She was mine to keep.

I nearly slammed headlong into the locked fire exit but managed to stop myself inches before it. The woman in black was nowhere to be found. I jogged back towards Mac and Millie’s, sure I missed another hall where the woman hid.

As I drew within a turn or two of their apartment, I heard Mac’s unsure voice, calling, “Kim? Kim? Are you still there? Please.”

My heart sank. I had failed to save her.

Tears streamed down Mac’s face but his eyes lightened as he saw me, like I was some kind of help, some kind of savior. I had failed. I was the opposite of a savior.

“I’m here,” I croaked.

“Thank god,” he said, “Millie… she’s stopped breathing. I didn’t know what to do.” He crumpled, all his weight falling into my arms.

I patted his back comfortingly then said, “There’s nothing to do now, Mac. She’s gone.”

Tears of my own flowed freely as I tried to break but something kept me upright, the memory of my terrible nightmare and the peace I felt when I finally said goodbye to my grandmother. I extricated myself from Mac’s sobbing form and lifted his face so I could look him in the eyes.

“It’s time to say goodbye, Mac.”

He nodded numbly and followed me inside to do what I never got to the chance to do, to do better than me.

Back home, I went straight to the bathroom, afraid I would vomit yet again but strangely, I was okay. I splashed cold water on my face as if to wash away the sadness of the day, of the ordeal I’d endured.

I looked into the mirror at my own face, focusing on my eyes, greener and brighter than I remember them in a long time.

“You did okay today, Kim,” I told myself. I picked up my grandmother’s white broach always displayed on the counter beside her picture and wrapped it around my neck.

Then, I saw the woman in black standing behind me in her long funeral dress and white broach that matched mine. The veil obscured her face again. She pointed directly at me and screamed.

Well Done Sir👌👌👌

Thank you 🙏🏻 and thanks for reading!